我提出一些看法給讀者參考

事實上 這篇有著"學習"的定義的問題

還有許多相關的重要觀念的釐清

一是學習過程到達穩定系統

另外是大量的關於"天才/專家"的學習與"記憶"的研究

The Myth of ‘Practice Makes Perfect’

How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Practice, practice. In a groundbreaking paper published in 1993, cognitive psychologist Anders Ericsson added a crucial tweak to that old joke. How do you get to Carnegie Hall? Deliberate practice.

It’s not a minor change. The difference between ineffective and effective practice means the difference between mediocrity and mastery. If you’re not practicing deliberately — whether it’s a foreign language, a musical instrument or any other new skill — you might as well not practice at all.

(MORE: Paul: How Your Dreams Can Make You Smarter)

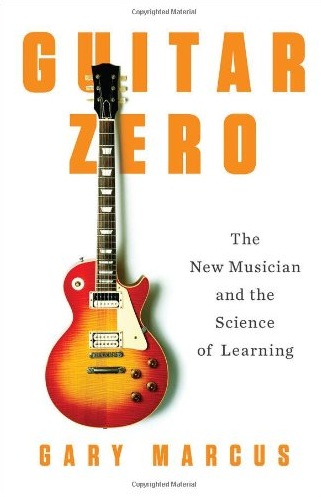

I was reminded of the importance of deliberate practice by a fascinating new book, Guitar Zero: The New Musician and the Science of Learning. Its author is Gary Marcus, a cognitive psychologist at New York University who studies how the brain acquires language. Marcus is also a wannabe guitarist who set out on a quest to learn to play at age 38. In Guitar Zero he takes us along for the ride, exploring the relevant research from neuroscience, cognitive science and psychology along the way. One of his main themes is the importance of doing practice right.

“Hundreds of thousands of people took music lessons when they were young and remember little or nothing,” he points out, giving lie to the notion that learning an instrument is easiest when you’re a kid. The important thing is not just practice but deliberate practice, “a constant sense of self-evaluation, of focusing on one’s weaknesses, rather than simply fooling around and playing to one’s strengths. Studies show that practice aimed at remedying weaknesses is a better predictor of expertise than raw number of hours; playing for fun and repeating what you already know is not necessarily the same as efficiently reaching a new level. Most of the practice that most people do, most of the time, be it in the pursuit of learning the guitar or improving their golf game, yields almost no effect.”

So how does deliberate practice work? Anders Ericsson’s 1993 paper makes for bracing reading. He makes it clear that a dutiful daily commitment to practice is not enough. Long hours of practice are not enough. And noodling around on the piano or idly taking some swings with a golf club is definitely not enough. “Deliberate practice,” Ericsson declares sternly, “requires effort and is not inherently enjoyable.” Having given us fair warning, he reveals the secret of deliberate practice: relentlessly focusing on our weaknesses and inventing new ways to root them out. Results are carefully monitored, ideally with the help of a coach or teacher, and become grist for the next round of ruthless self-evaluation.

(MORE: Paul: The Power of Smart Listening)

It sounds simple, even obvious, but it’s something most of us avoid. If we play the piano — or, like Marcus, the guitar — or we play golf or speak French, it’s because we like it. We’ve often achieved a level of competency that makes us feel good about ourselves. But what we don’t do is intentionally look for ways that we’re failing and hammer away at those flaws until they’re gone, then search for more ways we’re messing up. But almost two decades of research shows that’s exactly what distinguishes the merely good from the great.

In an article titled “It’s Not How Much; It’s How,” published in the Journal of Research in Music Education in 2009, University of Texas-Austin professor Robert Duke and his colleagues videotaped advanced piano students as they practiced a difficult passage from a Shostakovich concerto, then ranked the participants by the quality of their ultimate performance. The researchers found no relationship between excellence of performance and how many times the students had practiced the piece or how long they spent practicing. Rather, “the most notable differences between the practice sessions of the top-ranked pianists and the remaining participants,” Duke and his coauthors wrote, “are related to their handling of errors.”

The best pianists, they determined, addressed their mistakes immediately. They identified the precise location and source of each error, then rehearsed that part again and again until it was corrected. Only then would the best students proceed to the rest of the piece. “It was not the case that the top-ranked pianists made fewer errors at the beginning of their practice sessions than did the other pianists,” Duke notes. “But, when errors occurred, the top-ranked pianists seemed much better able to correct them in ways that precluded their recurrence.”

Without deliberate practice, even the most talented individuals will reach a plateau and stay there. For most of us, that’s just fine. But don’t delude yourself that you’ll see much improvement unless you’re ready to tackle your mistakes as well as your successes.

沒有留言:

張貼留言