Was Renowned Inventor of Suzuki Violin Method a Fraud?

Tuesday, October 28, 2014 - 02:00 PM

He developed a teaching method by which hundreds of thousands of children worldwide have learned to play the violin, cello, flute and piano. Alumni of the method include the violinists Hillary Hahn, Sarah Chang, Jennifer Koh and Leila Josefowicz.

But Shinichi Suzuki, the Japanese founder of the Suzuki Method who died in 1998, is now being accused of fabricating his personal story in order to help sell his books and courses.

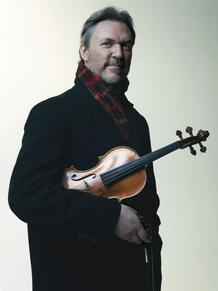

The violinist Mark O'Connor published a blog post last week asserting that Suzuki made up one of the key chapters in his life story, namely, that he spent eight years in the 1920s studying with renowned teacher Karl Klinger at the Berlin Conservatory. During that period, according to Suzuki’s biography, he played chamber music with Albert Einstein, who helped inspire his revolutionary teaching methods.

"I don't think it's true," writes O'Connor in a post titled "Suzuki's Biggest Lie." O'Connor presents an official document which he says shows that Suzuki failed his audition to the conservatory in 1923, at age 24. "Shinichi Suzuki had no violin training from any serious violin teacher that we can find," writes O'Connor. “He was basically self-taught, beginning the violin at the age of 18, and it showed."

O'Connor further alleges that Suzuki met Einstein only once and that a key endorsement from the legendary cellist Pablo Casals never occurred.

The Suzuki Method is based on a notion that by listening and imitation, children can learn to speak any language – and thus play music – by the age of three. While it has been dismissed by some critics as a sophisticated form of rote learning, it won international acceptance in the 1960s. According to the Talent Education Research Institute, an educational organization founded by Suzuki, about 400,000 children in 46 countries are now learning to play musical instruments through the Suzuki Method.

O’Connor’s allegations, which stretch over several previous blog posts, have sparked anger and confusion among Suzuki Method practitioners. Allen Lieb is a violinistwho teaches at the School for Strings in New York and studied with Suzuki during the 1970s. He says that Suzuki never claimed to have attended the Berlin Conservatory. "He studied privately with Klinger for seven years," Lieb says. "He was a personal student of [Klinger's]."

"Whatever is driving this, it's really causing a lot of concern among people," Lieb said of O'Connor's allegations. "They're just claims on his part. He seems to have gone personal in his attacks."

Lieb called O’Connor “a very talented performer" but suggested that “he has a financial stake in this, having just produced his own method."

Biographies of Suzuki – many very admiring in tone – corroborate the pedagogue's personal story, including his ties to Klinger and Einstein. In the 1981 Shinichi Suzuki: The Man and His Philosophy, author Evelyn Hermann describes Suzuki's studies with Klinger, which included not only intensive work on concertos, sonatas and chamber music, but also a personal friendship that included a visit to the teacher's summer home in Altmark, Germany.

O'Connor says that biographers merely repeated "the same concocted story" with "not a single one of them caring to check the facts. None of them picked up the phone to call Karl Klingler in Germany about it."

A representative at the Suzuki Association of the Americas declined to speak on record, but stated that Suzuki's personal story "really doesn't matter to us because the proof is in the pudding."