How Disruptive Innovation is Remaking the University

| Published: | July 25, 2011 |

| Authors: | Clayton M. Christensen and Henry J. Eyring |

Forum open for comment — 5 Comments — Post a comment

Executive Summary:

In The Innovative University, authors Clayton M. Christensen and Henry J. Eyring take Christensen's theory of disruptive innovation to the field of higher education, where new online institutions and learning tools are challenging the future of traditional colleges and universities. Key concepts include:

- A disruptive innovation brings to market a product or service that isn't as good as the best traditional offerings, but is less expensive and easier to use.

- Online learning is a disruptive technology that is making colleges and universities reconsider their higher education models.

About Faculty in this Article:

Clayton M. Christensen is the Robert and Jane Cizik Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School.

Editor's note: It has been more than a decade since the publication of The Innovator's Dilemma, in which Clayton M. Christensen introduced the idea of disruptive technologies—those unexpected products and services that shake up the market not because they are better than the traditional competition, but because they are are cheaper and easier to use. In The Innovative University, Christensen and Henry J. Eyring take the idea of disruptive innovation to the field of higher education, where new online institutions and learning tools are challenging the future of traditional colleges and universities. In this excerpt, they discuss the idea of a university's DNA.

In the absence of a disruptive new technology, the combination of prestige and loyal support from donors and legislators has allowed traditional universities to weather occasional storms. Fundamental change has been unnecessary.

In the absence of a disruptive new technology, the combination of prestige and loyal support from donors and legislators has allowed traditional universities to weather occasional storms. Fundamental change has been unnecessary.

That is no longer true, though, for any but a relative handful of institutions. Costs have risen to unprecedented heights, and new competitors are emerging. A disruptive technology, online learning, is at work in higher education, allowing both for-profit and traditional not-for-profit institutions to rethink the entire traditional higher education model. Private universities without national recognition and large endowments are at great financial risk. So are public universities, even prestigious ones such as the University of California at Berkeley.

Price-sensitive students and fiscally beleaguered legislatures have begun to resist costs that consistently rise faster than those of other goods and services. With the advent of high-quality online learning, there are new, less expensive institutional alternatives to traditional universities, their standing enhanced by changes in accreditation standards that play to their strengths in demonstrating student learning outcomes. These institutions are poised to respond cost-effectively to the national need for increased college participation and completion.

A disruptive technology, online learning, is at work in higher education, allowing both for-profit and traditional not-for-profit institutions to rethink the entire traditional higher education model.

For the vast majority of universities change is inevitable. The main questions are when it will occur and what forces will bring it about. It would be unfortunate if internal delay caused change to come through external regulation or pressure from newer, nimbler competitors. Until now, American higher education has largely regulated itself, to great effect. U.S. universities are among the most lightly regulated by government. They are free to choose what discoveries to pursue and what subjects to teach, without concern for economic or political agendas. Responsibly exercised, this freedom is a great intellectual and competitive advantage.

Traditional universities benefit society not just by producing intelligent graduates and valuable discoveries but also by fostering unmarketable yet invaluable intangibles such as social tolerance, personal responsibility, and respect for the rule of law. Each is a unique community of scholars in which lives as well as minds are molded. Pure profit-based competition would produce fewer of these social goods, just as increased government regulation would dampen the great universities' genius for discovery.

Ideally, the faculty members, administrators, and alumni who best appreciate the totality of the university's contributions to society will, in the spirit of self-regulation, play a leading role in revitalizing their beloved institutions. They have the capacity to determine their own fate and in so doing take the indispensable university to new heights.

In performing that critical task, they must understand not only current realities, especially the threat of competitive disruption, but also how universities have evolved over the past several hundred years. Even more than most organizations, traditional universities are products of their history. That history is shared, because most universities have emulated a handful of elite American schools that began to assume their modern form a century and a half ago. Prominent among them were Harvard, Yale, Johns Hopkins, Cornell, and MIT. Together, they have evolved to share common institutional traits, a sort of university DNA.

Much as the identity of a living organism is reflected in its every cell, the identity of a university can be found in the structure of departments and in the relationships among faculty and administrators. It is written into course catalogs, into standards for admitting students and promoting professors, and into strategies for raising funds and recruiting athletes. It can be seen in the campus buildings and grounds. These institutional characteristics remain the same even as individual people come and go.

Pioneering institutions such as Harvard and Yale first began granting Ph.D.s in the mid-nineteenth century. As graduates of their doctoral programs joined the faculties of other universities, they took their experiences and expectations with them. With the support of ambitious university presidents, they strove to make their new academic environments like those from which they had come. This internal drive was reinforced by external systems for accrediting, classifying, and ranking universities. It also became embedded in a common academic culture. As a result, even the smallest and most obscure universities bear many of the essential traits of the greatest ones.

Much as the identity of a living organism is reflected in its every cell, the identity of a university can be found in the structure of departments and in the relationships among faculty and administrators.

University DNA is not only similar across institutions, it is also highly stable, having evolved over hundreds of years. Replication of the DNA occurs continuously, as each retiring employee or graduating student is replaced by someone screened against the same criteria applied to his or her predecessor. The way things are done is determined not by individual preference but by institutional procedure written into the genetic code.

There is evolution in the university, though its mechanism typically is not natural selection of random mutations. As a general rule, the university alters itself only in thoughtful response to significant needs and opportunities. Entrepreneurism occurs within fixed bounds; there is rarely revolution of the type so often heralded in business or politics. This steadiness is a major source of universities' value to a fickle, fad-prone society.

Yet the university's steadiness is also why one cannot make it more responsive to modern economic and social realities merely by regulating its behavior. The genetic tendencies are too strong. The institutional genes expressed in course catalogs and in standards for admitting students and promoting faculty are selfish, replicating themselves faithfully even at the expense of the institution's welfare. A university cannot be made more efficient by simply cutting its operating budget, any more than a carnivore can be converted to an herbivore by constraining its intake of meat. Nor can universities be made by legislative fiat to perform functions for which they are not expressly designed. For example, requiring universities to admit underprepared students is unlikely to produce a proportional number of new college graduates. It is not in the typical university's genetic makeup to remediate such students, and neither regulation nor economic pressure will be enough, alone, to change that.

アイルランドのチーム「Team Hermes」

アイルランドのチーム「Team Hermes」  台湾の「NTHUCS」

台湾の「NTHUCS」  Eva Longoria氏(左から2人目)と「Team Rapture」

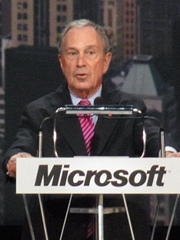

Eva Longoria氏(左から2人目)と「Team Rapture」  ニューヨーク市長のMichael Bloomberg氏

ニューヨーク市長のMichael Bloomberg氏